Note: this article focuses only on the PSM/RMP training burden that is unique to PSM/RMP. Furthermore, it does not address the requirements of training documentation.

Understanding the requirements of PSM/RMP training for Operators

The Training element in PSM (1910.119(g)) and RMP (40CFR68.71) requires that your process operators involved in operating a process receive certain training. For me, the key word for our understanding is Operator which means to control the functioning of a machine, process or system. If they turn valves, operate physical or electrical controls, etc. they are likely Process Operators. It is important to remember that the term Process Operator is not a title – it is a function. A management employee that turns refrigeration valves, or restarts equipment after a power failure is a Process Operator by function even if their title is “Director of Warehousing.” This concept is so important, that it is one of our PSM Golden Rules:

8. Treat people by their function within the process, not their title.

This means that in facilities where Contractors are actually the Process Operators, this Operator Training section must apply to them – just as it would a similarly situated direct-hire employee. OSHA made this clear in 1992:

…should a contract employer provide employees to operate a process, then those employees would obviously have to be trained to the same extent as the directed hire employees “involved in operating a process” under paragraph (g) of the final standard.

Generally speaking, all OSHA standards cover all employees including contract employees. In something of a break with tradition, the process safety management rule has separate provisions covering the training of contract employees. This was done primarily for emphasis since contract employees make up a significant portion of some segments of industries covered by the final rule. This is not to say, however, that paragraph (h) is the only section of the process safety rule that applies to contractors. As already indicated, under appropriate circumstances, all of the provisions of the standard may apply to a contractor (i.e., a contractor operated facility). After all, employees of an independent contractor are still employees in the broadest sense of the word and they and their employers must not only follow the process safety management rule, but they must also take care that they do nothing to endanger the safety of those working nearby who work for another employer. Moreover, the fact that this rule has a separate section that specifically lays out the duty of contractors on the job site does not mean that other OSHA standards, lacking a similar section, do not apply to contract employers. (OSHA, PSM Preamble, 1992)

Training in this element that training is broken into two categories: Initial and Refresher.

Initial Training

Initial training is 1910.119(g)(1)(i) – “Each employee presently involved in operating a process, and each employee before being involved in operating a newly assigned process, shall be trained in an overview of the process and in the operating procedures as specified in paragraph (f) of this section. The training shall include emphasis on the specific safety and health hazards, emergency operations including shutdown, and safe work practices applicable to the employee’s job tasks“

Initial Training is meant to cover the things Process Operators need to know to be involved in the covered process. It needs to cover an Overview of the Process as well as any specific Operating Procedures that the Process Operator is expected to perform.

One component of the Overview of the Process. Overview of the Process is simply how the covered process works. This understanding can be very basic or in-depth based on how much the Process Operator needs to know to safely perform the tasks assigned to them. This is the only component of the operator training requirements that is addressed by attending 3rd party classes (usually titled Refrigeration Operator) at a one-week school. I’m not discounting their value – I’m just pointing out that these schools do nothing to meet the other requirements of the training element. (Any honest school offering these classes will tell you this!)

This operator training must include a focus on:

- Specific Safety and Health Hazards of the process and work on the process.

- Emergency Operations and Shutdown.

- Safe Work Practices (Like LEO & LO/TO) applicable to the employee’s job tasks.

It’s important to emphasize that this training is conducted before the operator actually performs these tasks independently. For a typical Ammonia Refrigeration Process Operator, these requirements would lead us to train, at a minimum, in the following areas:

- Routine refrigeration system operation; an overview of the process.

- Ammonia properties, safety and health hazards

- SOP awareness including the requirement to follow written SOPs

- Specific training in any SOP they are expected to perform such as the Overall System Operation SOP(s), which includes emergency and normal refrigeration system operation procedures.

- Their individual role in the emergency response plan

In many programs, this is a level of Process Operator called Entry Level. Due to the increased use of Contractors in most Ammonia Refrigeration processes, many, if not most, Process Operators are never trained to reach higher levels of operator classification.

Refresher Training

1910.119(g)(2) – “Refresher training shall be provided at least every three years, and more often if necessary, to each employee involved in operating a process to assure that the employee understands and adheres to the current operating procedures of the process. The employer, in consultation with the employees involved in operating the process, shall determine the appropriate frequency of refresher training.” Note that this training is meant to reinforce the earlier emphasis on SOPs.

Refresher or Ongoing Training is a collection of activities designed to reach a certain Performance-Based goal: …To assure that the employee understands and adheres to the current operating procedures of the process.

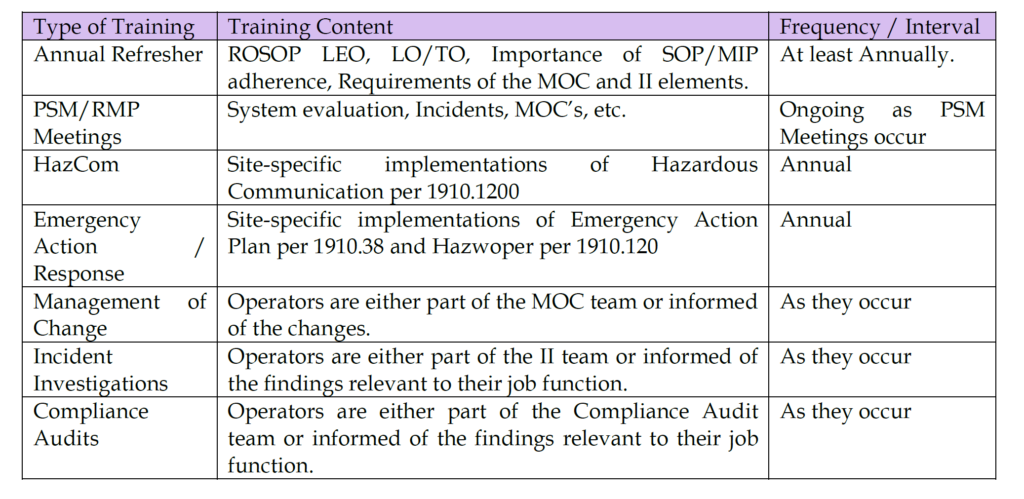

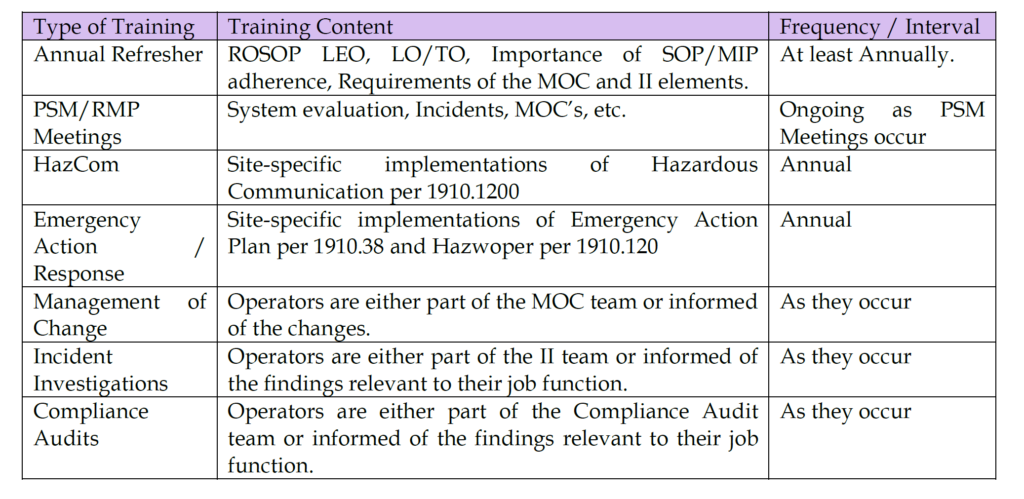

The “understands” portion of the performance basis should have been handled by our Initial Training. The real question then is how we ensure Process Operators adhere to current operating procedures of the process. This is called Operational Discipline. Much of what we call Refresher Training is just reminding Process Operators about the importance of this Operational Discipline. An example Refresher Training schedule is below:

In addition to the above regularly scheduled and event-driven training, there should be some sort of verification that process tasks are being completed in accordance with the written procedures of the process. On a regular basis (usually at least annually) the Responsible Person should verify that qualified operators are adhering to the SOPs. This verification usually takes the form of observations while the operator performs their assigned work. These observations should be done without prior notification of the operator being evaluated.

While there is a requirement that Refresher Training occur at least every three years, and that the frequency of the training be decided in consultation with the Process Operators, an effective PSM/RMP Program is continuously Training and seeking consultation.

Employers, in consultation with employees, shall determine the appropriate frequency, which may be based on consideration of such factors as deviations from standard operating procedures, recent incidents, or apparent deficiencies in training. (OSHA, CPL 2-2.45A, 1994)

Mechanical Integrity (Maintenance) Training

1910.119(j)(3) – “Training for process maintenance activities. The employer shall train each employee involved in maintaining the on-going integrity of process equipment in an overview of that process and its hazards and in the procedures applicable to the employee’s job tasks to assure that the employee can perform the job tasks in a safe manner.”

In this section they are referring not to the SOPs so much as the written procedures required in 1910.119(j)(2) – “Written procedures. The employer shall establish and implement written procedures to maintain the on-going integrity of process equipment.”

The rule requires that there be written procedures on maintaining the integrity of the covered process and that the personnel performing these procedures be trained in those procedures. Most chemical and petroleum plants have one set of personnel to operate the plant and another to maintain it. Nearly all Ammonia Refrigeration systems have the same personnel operate and maintain the process, so most plants in our position combine these training requirements with the Operator Training requirements.

As OSHA indicated in the preamble, paragraph (j)(3) requires that employers provide maintenance employees with “on-going” or “continual” training adequate “to assure that they can perform their jobs in a safe manner.” In this regard, the paragraph clearly contemplates that new maintenance employees be trained before beginning work at the site, and all maintenance employees receive additional training appropriate to their constantly changing job tasks. (OSHA, CPL 2-2.45A, 1994)

Appendix C to the rule notes that the “employer needs to develop procedures to ensure that tests and inspections are conducted properly and that consistency is maintained even where different employees may be involved. Appropriate training is to be provided to maintenance personnel to ensure that they understand the preventive maintenance program procedures, safe practices, and the proper use and application of special equipment or unique tools that may be required. This training is part of the overall training program called for in the standard.” (OSHA, 29CFR1910.119, 1992)

Note that this includes contractors that are performing MI tasks on the covered process:

This training requirement applies to both host employer’s and contractor employer’s employees performing MI procedures. CPL 02-02-045, Appendix B, pg. B-27, states, “If contract employees are involved in…maintaining the on-going integrity of process equipment, then they must receive training in accordance with specific training requirements set forth in paragraphs (g) and (h), respectively”). (OSHA, Refinery PSM NEP, 2007)

What does a successful training program look like?

A successful Operator Training element will be one that:

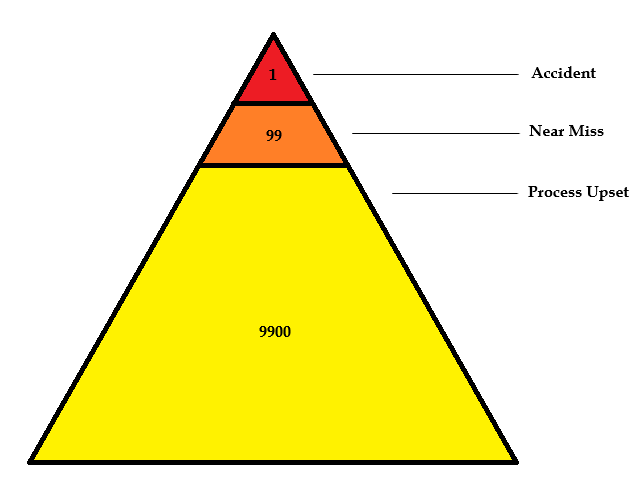

- Ensures the operators are aware of the procedures and will consistently apply those written procedures resulting in fewer process deviations.

- Ensures the operators understand the process and the procedures so they are able to quickly correct those few deviations that do occur.

“An effective training program significantly reduces the number and severity of incidents arising from process operations, and can be instrumental in preventing small problems from leading to a catastrophic release.” (OSHA, CPL 2-2.45A, 1994)