The Situation: Several times a month I get a call from a recruiter or a facility that desperately needs to fill a PSM coordinator position. They quickly learn something that many people in our industry are unaware of – quality PSM practitioners are rare, usually already employed and very expensive!

Now, it’s certainly possible to entice someone out of their current job, but it’s going to be a very expensive proposition. If you need somebody right away there aren’t many other options, but if you have time to plan for the PSM coordinator/manager position, there is often a much better solution: Build your own!

That’s right – take someone you already have in your organization, someone who already possesses the hard to replicate skills, and then train them into the job. Interested? Let me show you how it can be done! First, we have to identify the skills…

The Skills: I’ve visited a hundred or more PSM covered processes and audited just about every kind of PSM program for Ammonia Refrigeration. After a while, you start asking yourself: “Is there a common thread?” to what works and what doesn’t. There seems to be a certain type of person that does very well in the PSM role. These aren’t people who end up hating their PSM duties – they are people who come to love them! These people have a few common skills. While these skills aren’t the ones that many people think of when dealing with PSM, in my experience, they are the ones that often decide between failure and success.

- Curiosity – Why do we work this way? How does that work? Who should be doing this? That’s right, plain old curiosity is a rare thing these days. I’ve been to bottling plants and asked the line operator who worked there for a decade how many bottles his machine processes an hour, only to find out that it never occurred to him to ask. This is not the kind of person you want in your PSM role! You need someone who is intensely curious. You need the kind of person who will spend a half day doing internet searches on “Maximum Intended Inventory” before feeling comfortable that the issue is covered in your program. It’s the kind of person that says: “Well, it’s asking for Maximum Intended Inventory and this document has those words in the title, so we must be good” that get you into trouble.

- Detail Oriented – I’m not talking about typical levels of detail. I’m talking about an almost pathological need for order and accuracy. Oddly, every single PSM coordinator I know that is good at what they do obsesses about document formatting. That sounds odd, doesn’t it? I think it actually points to something more important: the kind of person that notices the fonts don’t match, that the margins are off, or that the bullet points don’t line up, is also the kind of person that is going to notice much more important things, like incorrect valve numbers. Detail oriented people are also good at taking notes – the kind of notes that actually document what happened in a meeting rather than notes that look like a bad powerpoint rendition of the meeting.

- Technically Proficient – I’m not talking about technical proficiency in Ammonia refrigeration. I mean that this is the kind of person who is willing to pick up a manual and set the time on their microwave after a power outage. If you’re the kind of person who has a houseful of electric clocks blinking 12:00, that doesn’t make you a bad person; it’s just not likely you will be a good PSM coordinator. Most important though is the ability to translate the written word into action. You see, as a PSM coordinator that’s exactly what you need to happen – the policies, guidelines and procedures need to become reality through the actions of the people operating the system. If you can’t take the written word and apply it, then you aren’t going to be able to take the action and document it in the written word either.

- Computer Skills – I’ve trained operators to write SOPs all over the country and the biggest hurdle is always getting them to use a computer to write. It’s as painful to watch most operators type as it is for them to watch me work on a car engine – and nearly as futile. You see, the skills that you need to create, modify and manipulate documents in Word, Excel, etc. are not in any way useful to the average blue-collar mechanic. For that reason, they don’t bother to develop them – and frankly it would be a waste of time for most of them to do so. They already have valuable skills and their time is better spent honing the skills they already possess or building new ones that complement those skills. Just as there are people who specialize in maintenance, there are also people that specialize in working with computers to produce and manage documents.

- Personal Skills – They don’t need to have been voted prom queen/king, but they need to be able to work with people across all levels of the organization. They also need to be able to work with outside vendors, consultants, government officials, regulators, etc. in a professional capacity.

Ok, from what I’ve seen, that’s the list. That’s the skillset that pretty much defines success in the Ammonia Refrigeration PSM role. I am pretty sure you don’t have anyone like that in the maintenance department. In fact, most food or cold storage plants don’t have many people like that in their buildings, let alone their maintenance department. Where are you going to find someone like that?

One Possible Solution: You’ll have to go to a place where those skills are rewarded, where people are hired and retained based on those skills. Do you know where that is in your facility? Believe it or not, most companies have someone they can train into a good PSM coordinator sitting around answering phones and scheduling appointments. That’s right: somewhere you have a standout secretary/personal assistant who has the raw material to be a good PSM coordinator.

Perhaps you are saying to yourself: But secretaries don’t know anything about Ammonia Refrigeration! Well, you’re right; but the reality is that it’s fairly easy to teach a curious, detail oriented, technically proficient person with computer skills what they need to know about Ammonia Refrigeration. It’s certainly a lot easier than it is to teach most Ammonia Refrigeration Mechanics all of those other skill sets that a secretary already has. Remember, we’re not trying to turn this secretary into a great refrigeration mechanic. We just need this new PSM coordinator to know enough about the process that they aren’t stepping on mechanic’s toes or devising silly policies.

A Challenging Transition: How would we make that transition? Well, to make the rest of this conversation easier, let’s imagine a fictional character named Natalie who is already a fairly competent secretary / personal assistant. She’s been with the company for over five years and has a track record of success – she’s a known quantity, something that can’t be said for some outside hire with a fancy resume. She’s got all the requisite skills we’ve outlined above and it turns out she’s sort of bored to tears in her job. It’s obvious if you think about it – she’s already involved in every volunteer committee the work place has to offer. She is always trying to help people out and her role in the office exceeds the actual scope of the job because she’s just the “go-to” person when you need something done.

The Maintenance Manager approaches Natalie with this unique career change. She’ll get to move out of the office and closer to the action – where the products are being made. As we said, Natalie is interested in a challenge, but she wasn’t so unsatisfied that she was looking for another employer. She readily accepts because this opportunity allows her to grow professionally while keeping all her seniority, benefits, vacation time, etc.

A Realistic Training Plan: We’re not going to throw Natalie to the wolves here – we have to train her to do the job she’s been assigned to do. We’re going to start with a little “overview of the process” training. That’s essentially going to involve following around our lead refrigeration technician for two weeks while he/she does the job of a refrigeration mechanic. We’re just trying to get her a little familiarity at this point so we’ll encourage her to ask questions but we’re not expecting any actual hands-on work out of her at this point.

After this two week familiarity training, we’ll pack Natalie off to a 4-day Operator 1 class at a quality ammonia school like GCAP. At the school she’ll learn the basics of refrigeration – how and why it works. Once she’s back from her training, we’ll put her back on shadow duty with that lead refrigeration technician but this time we’ll encourage her to get her hands a little dirty: Maybe help drain some oil pots, swap out filters or coalescers, clean out condensers, etc. We’re not really expecting Natalie to become a mechanic here – we’re just trying to make sure she gets a feel for the tempo and nature of the job.

When the technician is doing things that Natalie has already done, she’ll be expected to spend that down-time familiarizing herself with the existing PSM documentation. When we feel she’s ready (likely just few weeks) we’ll send her off again for some PSM training. (I am admittedly biased because I teach PSM at GCAP, but in all honesty there is no PSM course for Ammonia Refrigeration that holds a candle to the course GCAP provides). By waiting a few weeks to allow Natalie to familiarize herself with the job and the equipment, we’ve really set her up for success at this class!

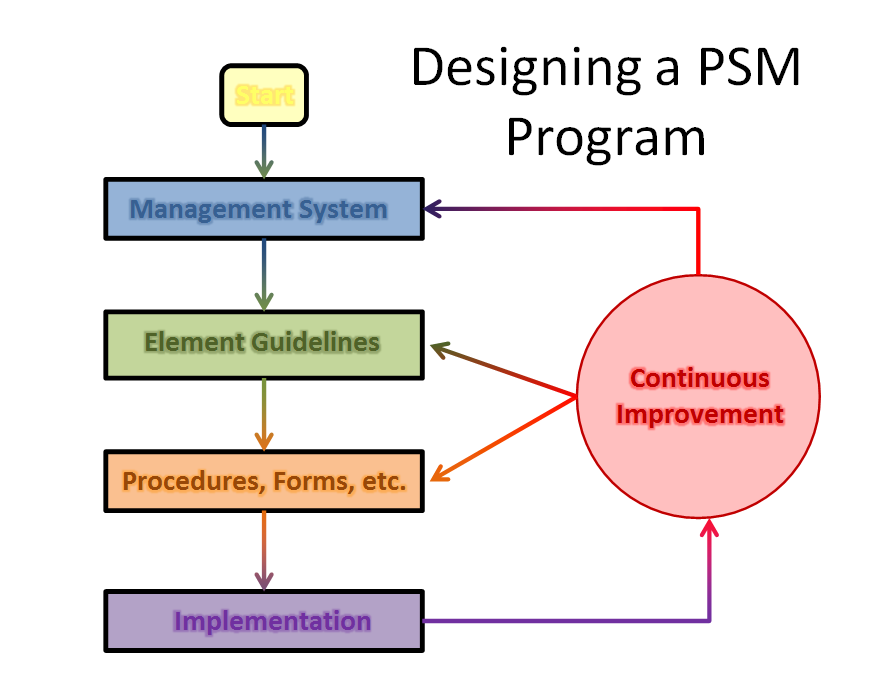

When Natalie comes back from her training, we’ll ease her into the role of PSM coordinator, starting off by having her perform a Gap Analysis on the PSM system. In this Gap Analysis she’ll compare the requirements of the PSM standard she’s learned and the examples GCAP provided with her documentation at the facility. She’ll list the deficiencies, prioritize them and bring them to the management team. Natalie has just set herself up with a good 3 months’ worth of training/work!

Conclusion: You see how this would all work? I know it works in the real world, because I’ve seen it work across the country. The problem our industry faces is that the kinds of people who make great PSM coordinators are generally not the kind of people who gravitate to maintenance departments. Most of the people who have the right skills aren’t even aware that Ammonia Refrigeration and PSM even exist! You’re going to have to go out there and find them, bring them in, and start them off on a uniquely rewarding career.